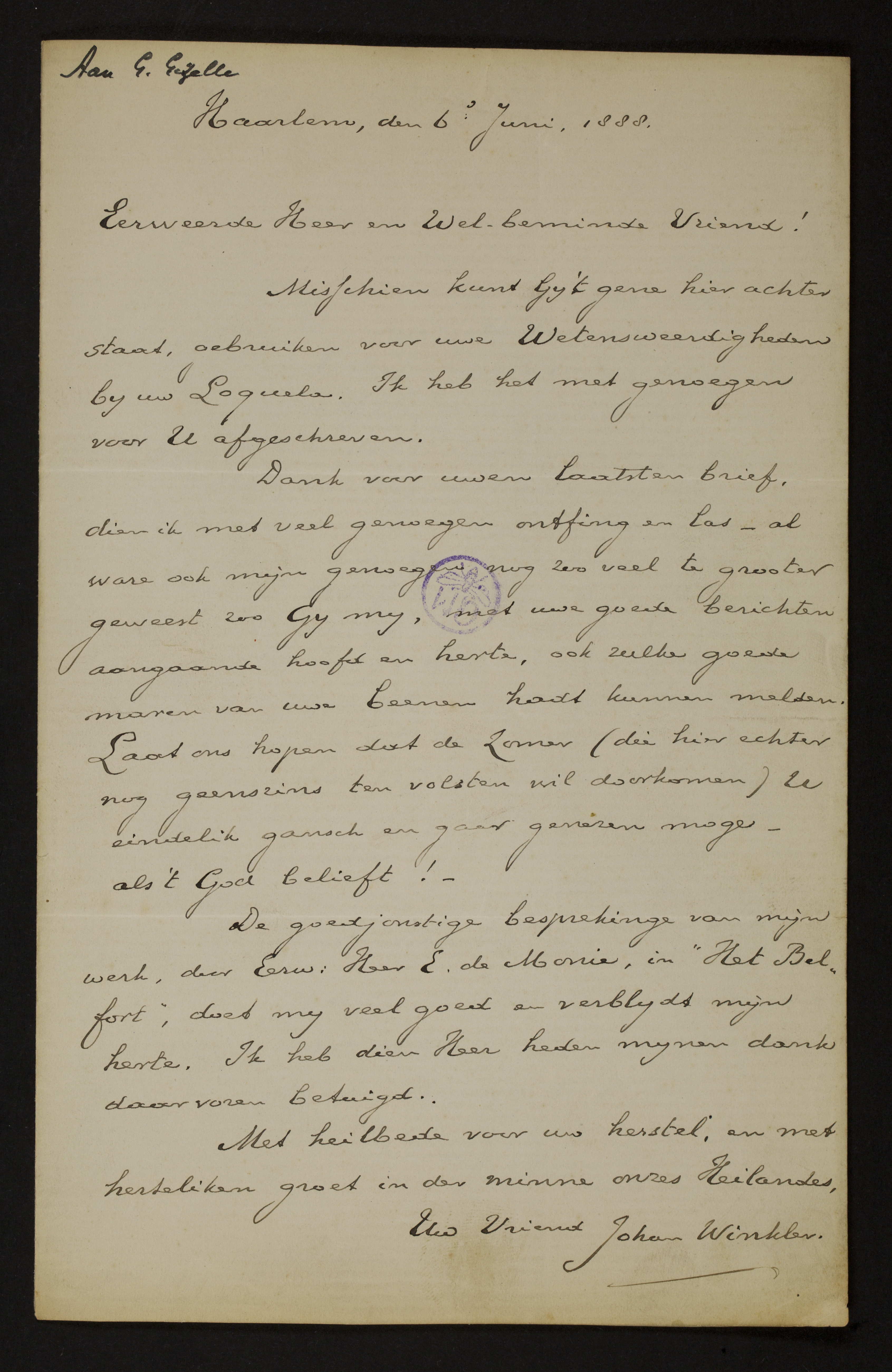

Misschien kunt Gij 't gene hier achter staat, gebruiken voor uwe Wetensweerdigheden bij uw Loquela. Ik heb het met genoegen voor U afgeschreven.

Dank voor uwen laatsten brief, dien ik met veel genoegen ontfing en las - al ware ook mijn genoegen nog zoo veel te grooter geweest zoo Gij mij, met uwe goede berichten aangaande hoofd en herte, ook zulke goede maren van uwe beenen hadt kunnen melden. Laat ons hopen dat de zomer (die hier echter nog geenszins ten volsten wil doorkomen) U eindelik gansch en gaar genezen moge - als 't God belieft! -

De goedjonstige besprekinge[1] van mijn werk, door Eerw: Heer E. de Monie, in "Het Belfort", doet mij veel goed en verblijdt mijn herte. Ik heb dien Heer heden mijnen dank daar voren betuigd.

"It was only with the introduction of Christianity that a copious Latin vocabulary, chiefly referring to ecclesiastical affairs, found admission into the language of the country. With the scholastic, and subsequently the classical studies, new supplies of Latin terms were introduced into the vernacular; and the mania of latinizing the language in the time of Queen Elizabeth became so general, that Thomas Wilson (died 1581) bitterly complains of the "strange ink-horn terms" introduced into English."[2] Some seek so far for outlandish English, that they forget altogether their mother's language. And I dare swear this, if some of their mothers were alive, they were not able to tell what they say; and yet these fine English will say they speak in their mother's tongue, if a man should charge them with counterfeiting the King's English." And of Sir Thomas Browne it is asserted not without reason that to persons acquainted only with their native tongue, many of his sentences must be nearly unintelligible; and the author is himself of opinion that if the desire after elegancy continued to work in the same direction, it would soon be necessary to learn Latin in order to understand English." -

(Uit: Helfenstein, A comparative Grammar of the teutonic languages. - London, 1870. - bladzijde 8.)[3]